Declaring Your Documentary’s Central Thesis

In celebration of my 50th birthday, I’m taking a cruise to Alaska. During my vacation, I want to share with you one of my most popular and useful blog postings from 2010. Many filmmakers wrote in to say how valuable they found this structural technique.

Have you ever watched a documentary that meandered so much you wondered if the filmmaker was on her own little acid trip?

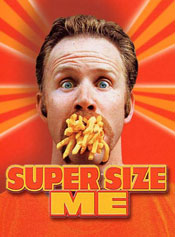

Most of the topic-based documentaries that are showcased at the big festivals, screened theatrically and/or broadcast on television (“Supersize Me”, “Religulous” and “Who Killed The Electric Car?”) don’t suffer from a meandering structure. But if you’ve ever been to smaller, more niched film festivals, you’ve probably run into a documentary plagued with a chaotic approach to its topic.

And the problem often stems from the director having failed to identify and declare the film’s central thesis. The central thesis is generally a simple idea, such as “big food companies don’t want you how poorly they treat the environment”. This statement, for example, is the central thesis for the documentary “Food, Inc.”

While you may know what your film’s thesis statement is in your bones, that doesn’t help your viewer if you don’t set up your thesis statement to stand out in neon, to practically shout to your audience, “Listen up! Here’s the big idea!”

I want to share several techniques that can help you to elegantly broadcast your film’s central idea. (Note that a documentary’s central thesis can also be posed as a central question.)

1. State your film’s central idea as text on screen. This works particularly well if you have been using spoken narration and suddenly switch to text. When text on screen gets “read aloud” in the viewer’s head, the volume gets turned up.

2. Repeat the film’s central idea when it’s first presented and also remind the audience of the central idea throughout the film. Repetition spells emphasis, which spells clarity. Repetition spells emphasis, which results in clarity.

3. Preface your central idea with words that herald something big, such as “key”, “most important,” “central,” etc. For example, in a film about the cause of autism, imagine you open the film with shocking statistics about the rise in autism in Western societies. You could then set up the central question with a line of narration such as, “The escalating number of neurologically challenged children born today has scientists, psychiatry professionals and even environmental activists all asking the same key question: ‘What is causing an epidemic of autism?’”

Your film would then go on to explore the various theories.

4. Punctuate your central thesis with sound FX or a music sting. Your composer can help you “rev up” to stating your central thesis, or emphasize its importance with a strong musical exclamation point after it’s been stated.

5. Pose your central question in a man-on-the-street (MOS) montage. In the documentary “Supersize Me”, filmmaker Morgan Spurlock asks people on the street if they think McDonald’s food is healthy. Getting several answers to one ridiculous question reinforces the question’s gravity. Soliciting opinions can also add humor to the moment, and humor helps us remember things.

6. Use the film’s title to state the film’s central idea or question. You can see this technique at work in the film titles “Who Killed the Electric Car?” and “An Inconvenient Truth”. In the latter example, the title refers to the central thesis that “global warming is real”.

7. Create a graphic that reinforces the film’s central idea. I highly recommend watching “Who Killed the Electric Car” to study how the guilty/verdict graphic functions to set up and answer the central question.

8. If you’re making a personal documentary and your quest is to find out something, then set up the central question (your quest) with a statement such as “I wanted to find out why/how X…..” The “I want” signals to the viewer that the film’s narrative backbone is about to be revealed. And if your quest lends itself to an idea-based film, then crafting what I call “the protagonist’s statement of desire” (the “I wanted” statement) can orient your viewer to the film’s central question, which is the burning question you want answered or the mystery you want to solve.

You may worry that some of the above approaches are hitting the audience over the head with your message, but in my experience viewers appreciate clarity–and are not so forgiving of murky thinking. Just as a professional narrator will speak a notch louder and more animated than the untrained voice, so your film’s central idea must be projected boldly to your viewer.

Once you state your documentary’s central thesis near the top of your film, you will spend the bulk of your film proving it. Or, if you’re posing a central question, you’ll spend the majority of your film answering it.

For more information on structuring documentary films, check out my e-course “The Ultimate Guide to Structuring Your Documentary.” If you want to buy it, I’ll give you $100 off since the group calls have passed, but you’ll need to email Karen@newdocediting.com for this discount. (Don’t buy through the shopping cart). Note that I will be taking this course down soon, so don’t delay. Find out more at: https://newdocediting.com/land/ultimate_documentary_guide/